Winter Oak

26 Apr 2024 | 9:13 am

1. The world out of kilter: being modern

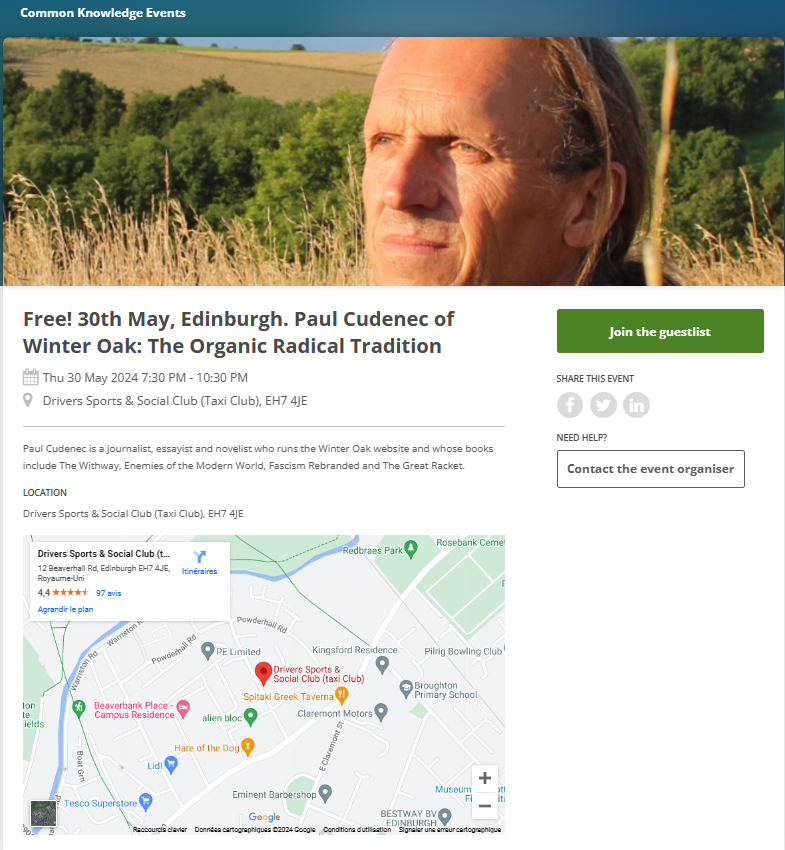

by Paul Cudenec

To be modern is to accept that which you should refuse; to adapt to evil rather than to resist it.

To be modern is to have been melted down and poured into somebody else's mould.

To be modern is to have forgotten how to remember.

To be modern is to be more detached from nature, more helpless, more dependent, more wasteful, more destructive, more short-sighted than your ancestors could ever have imagined, and yet to feel proud of yourself and your era.

To be modern is to prefer artifice to organicity, surface to depth, quantity to quality.

To be modern is to have absorbed so many meaningless facts that there is no more room in your head for meaningful knowledge.

To be modern is to turn your back on common sense and conform to the collective insanity.

To be modern is to be convinced that all change is necessarily good and to refuse to recognise the instinct that tells you otherwise.

To be modern is to be at home both everywhere and nowhere; to be somebody and nobody; to be still alive and yet already dead.

See also: The world out of kilter: occupation and zombification

Coming soon: The world out of kilter: reclaim our lives!

24 Apr 2024 | 9:50 am

2. Modernity as Fragmentation (Revolutionary Aristotelianism Part 4)

by W.D. James

Riders on the storm

Riders on the storm

Into this house we're born

Into this world we're thrown

Like a dog without a bone

An actor out on loan

Riders on the stormi

– Jim Morrison, Riders on the Storm

In the lines above, Jim Morrison lyrically presents an 'existentialist' take on human existence. We're 'thrown' into the world. It's a fundamentally absurd situation: we seek meaning, but the cold universe revealed by science offers no meaning. We're 'riders on the storm', trying to create values for ourselves and use them to make some sense of life, but there are no safety nets: live on the highwire as best you may; the abyss opens beneath you.

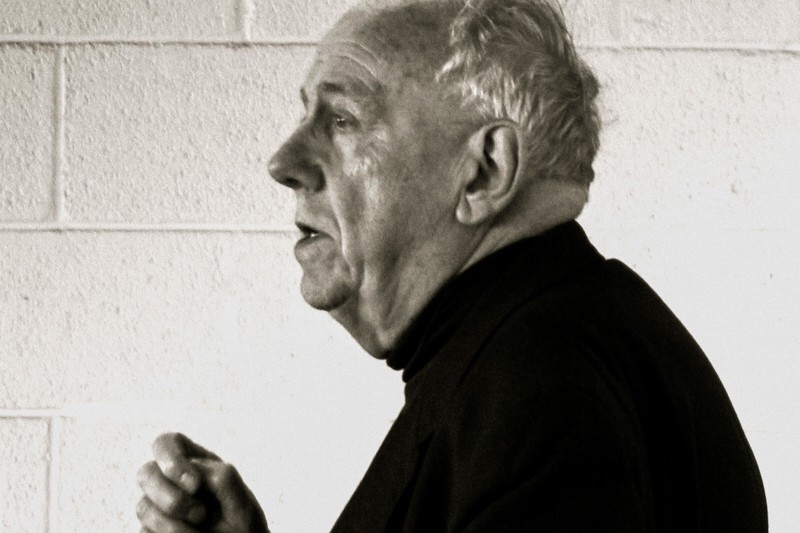

Such a solution is completely untenable for the moral philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre. He was born in Scotland in 1929. In his childhood, he became acquainted with old-style skilled craftspeople in his native land and in Ireland. The crews of fishing boats plying their traditional trade, and operating in intimate cooperation with one another, have remained a model of what a sound community might be like, in his view.

MacIntyre became a Communist in early adulthood, but switched over to a form of Trotskyism in the early 1950s when the abuses of Stalinism became apparent. Later, in the 1960s, he was one of the founders of the 'New Left' in England, editing a couple of important journals in that movement. In the 1970s he surprisingly moved to the United States and eventually converted to Catholicism. He has taught and lectured at a number of institutions including Oxford, Princeton, Duke, Vanderbilt, Yale, and Notre Dame, among many others.

With the publication of After Virtue in 1981, he reintroduced a version of virtue ethics and revolutionized academic philosophy in the process. His thinking and writing since that time represents an ever-deepening reappropriation of Aristotle into academic philosophical discourse. He would typically be considered to operate at the very highest levels of recent academic thought, especially in the areas of ethics and political philosophy. Unfortunately, MacIntyre, at least in terms of how he writes, is very much in the modern Anglo-American style of philosophy which tends to be rather precise, arid, and has difficulty breaking out of its academic boundaries. In this and the following essays I'll attempt to present some of his ideas in an accessible manner and show why he is so relevant to our contemporary quandaries.

Fragmented Ethics

At the opening of After Virtue, MacIntyre asks us to imagine a situation in which the natural sciences suffer a catastrophe. In his scenario, an enraged public holds the natural scientists responsible for a deepening environmental crisis and many scientists are killed, labs burned, etc…. Eventually, a few shards of what science has revealed about the world are collected up here and there. Some propositions of Euclid, some bits of physics, maybe a few shards of evolutionary biology. These salvaged fragments are held in high esteem and sort of made into totems.

Ultimately people want to make sense of the material world again, and they have no recourse but to fall back on these few truths. They attempt to put them together, but the result is far from satisfying. The problem is that the practice of science has ended. The living tradition of 'doing science' is broken. The remaining elements are recognized as valuable, but they aren't living. You can't put Humpty Dumpty back together again. Imagine how such a world would be different from the world we are used to.

He then drops the bombshell of stating that this is analogous to what has happened to our moral discourse. Once, as a civilization, we pretty much had a shared tradition of moral thought, but we intentionally destroyed that, then figured out you really can't get along with without morality, but are not able to reassemble a coherent and shared moral picture of the world. He laments, "There seems to be no rational way of securing moral agreement in our culture."ii

On his account, we moderns are forced into a position of 'emotivism.' This is the basic assertion that values are personal and subjective and 'what might be right for you might not be right for me.' Morality is about what we feel. The problem is we often feel different things and if our moral vocabulary is not subject to rational debate, we aren't left with moral means to work through our differences. Ultimately it devolves to issues of power: we don't agree, but we who hold one view can wield political power to get our wills imposed…until we can't. Either way, ethical disagreements don't get worked out through ethical discourse. As an approach to ethics, "Emotivism thus rests upon the claim that every attempt, whether past or present, to provide a rational justification for an objective morality has in fact failed."iii

MacIntyre wants to show that just as there was a sociological basis to living scientific inquiry, which was wiped out in his hypothetical example, there is a sociological basis to moral reasoning which has in fact been wiped out, but which might be reconstituted. He observes that, "In many pre-modern, traditional societies it is through his or her membership in a variety of social groups that the individual identifies himself or herself and is identified by others."iv

It's important to get the distinction he is drawing here. In our modern world, we are encouraged to think of ourselves as separated individuals. More importantly, our societies and polities think of us in this way. MacIntyre's assertion is that in pre-modern societies people were thought of more as persons than individuals. A 'person' is the individual plus their social relationships. The modern world has "bifurcated" our existence between who we are as individuals and the social relationships, which are held to be rather arbitrary, and our broader society. His fundamental claim is that if we separate out our individual selves from our larger social context we cannot reason together morally about the things that are social by nature. As modernity erodes our shared social existence it also erodes individual identity and the capacity for a shared moral framework.

Weber, Nietzsche, or Aristotle

Our modern world, he asserts, offers us basically two alternatives. The modern State and the capitalist Market have eradicated all that is local, specific, and good. In the wake of that we may be Weberians or Nietzscheans. Max Weber is known as the "iron cage of bureaucracy" guy. His argument was that as organizations become ever larger, more and more of life would be subsumed under the auspices of rationalized bureaucratic administration. He saw that this was dehumanizing but thought it our fate. This is the world where ethical concerns are written into government administrative codes (the parts of the law that were never passed by legislatures but are written by the governmental agencies charged with implementing legislative acts), corporate ethics codes, and things like that. The organization has certain things it means to achieve. It needs to set the boundaries of what is and is not acceptable behavior. Ethical concerns are reduced to rules whose ultimate legitimacy rests on nothing more foundational than the rules someone wrote down. 'Should I do this?' is reduced to 'am I allowed to do this?' For instance, here the intricacies of romance and seduction are reduced to 'continuous consent.'v

Alternatively, we might be Nietzscheans. On MacIntyre's account this is an authentic option, but it just doesn't work. He breaks down that option along the following lines: "The underlying structure of his argument is as follows: if there is nothing to morality but expressions of will, my morality can only be what my will creates. There can be no place for fictions such as natural rights, utility, the greatest happiness for the greatest number. I myself must now bring into existence 'new tables of what is good.'"vi How would I do that exactly? Even if I succeed in somehow conjuring values out of my will, you will be doing the same, and so on and on. There are no shared bases for holding values in common. Except, that is, power. For Friedrich Nietzsche ultimately the will of those who can rise above the "herd" is to define the values of the many: "the will to power" is one of his central concepts.

Instead, MacIntrye advocates a retrieval of pre-modern moral discourse. Specifically, Aristotelian discourse. He observes: "Within the Aristotelian tradition to call x good (where x may be among other things a person or an animal or a policy or a state of affairs) is to say that it is the kind of x someone would choose who wanted an x for the purpose for which x's are characteristically wanted…. To call something good therefore is also to make a factual statement."vii Think of our example in a previous essay: Sally the Thoroughbred was 'good' because she did what we want thoroughbreds to do. Because of its ability to discuss values as facts, "Aristotelianism is philosophically the most powerful of pre-modern modes of moral thought. If a premodern view of morals and politics is to be vindicated against modernity, it will be in something like Aristotelian terms or not at all."viii

He notes that on the original formulation of Aristotle, and even more so on the formulation of the medieval interpreter of Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, the issue of morality and virtue was situated within an overarching "cosmic" scheme which assured that as moral reasoning occurred from a bottom-up perspective, it was assumed this would ultimately coalesce universally. In this work, MacIntyre expressly sets out to reinterpret Aristotle's moral theory without reference to his teleological biology. He accepts that that may be a bridge too far for we moderns. As a result, his formulations will be somewhat limited in their completeness. MacIntyre later admitted this as a philosophical error on his part and worked to bring biology, and hence human nature, into the picture again. We'll see how that works in the sixth essay of this series.

Phronesis

MacIntyre affirms that "the political community as a common project is alien to the modern liberal individualist world."ix Central to the functioning of a community thus conceived is the ability for its members to engage in genuine dialogue on matters of 'practical rationality', which includes our morality. Aristotle had termed the sort of wisdom represented in good practical reasoning 'phronesis'. The person who possesses phronesis knows what is due them (the central knowledge required for the practice of justice). More broadly, it refers to the ability to reason about particular cases: what is due to people in the particular circumstances we currently find ourselves in?

It is the inability of modern conceptions to access moral facts which precludes the ability of modern individuals and modern societies from actually engaging in moral reasoning. So, when next time we look in detail at exactly how he reformulates Aristotle, we can keep in mind that it is reinvigorating our ability to reason together about a shared morality that will be driving his theoretical project.

The Spirit of Association

In the 1830s, Alexis de Tocqueville, a French aristocrat and one of the founders of modern sociology, set about to understand America. He felt confident that 'democracy' was pretty much fated to increase in the modern era (as opposed to monarchy or aristocracy). His concern was that popular revolt in the French Revolution had quickly turned into The Terror and led to the imposition of authoritarian rule by Napolean. However, America seemed to be building a relatively stable and prosperous democratic society. What was different?

He would publish his findings as Democracy in America. Essentially the difference he discovered was that France had largely lacked a set of intermediary institutions between the mass of individuals at the bottom and the state on top. This led to instability and the ability of demagogues to motivate the masses to all sorts of destabilizing actions. American culture, however, was characterized by the "spirit of association". Though it was already a large country, the national government was weak. Most politics were carried out at the township and village level. Americans, still pushing the boundary of the frontier westward, typically did not sit about and wait for 'the government' to do things for them. If they wanted to educate their children, they built a one-room building and hired a teacher. If they wanted access to books they started a library, usually by subscription. If they wanted some religion, they built a wooden church and hired a preacher, or possibly paid part of the salary of a circuit-riding preacher who would ride between a number of churches, preaching as he arrived at each.

Of course, those intermediary institutions have pretty much become huge operations or have had their functions subsumed by the state. Americans are no longer 'joiners'. We went Weberian long ago. However, even in my childhood years, the culture of self-governance was not dead. It was not uncommon for a person with just a high school education to run a business or be employed as a skilled worker. Probably they served in some office of their local church, or played the organ, or otherwise had a respected social role there. They probably belonged to a couple of civic associations: a fraternal order, a charity, or what not. They knew (and had known their whole life) the township commissioners and could expect to go talk to them and get something done if they had a zoning issue or something along those lines.

This is all largely past. There is the mostly unassociated lot of us and the state and its administrative agencies. And big corporations. This is the apocalypse MacIntrye sees as having undercut our culture and communities which makes shared moral reasoning among us impossible.

i It is an amazing song: Riders on the Storm – The Doors HD (youtube.com)

ii Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue, 2nd ed., University of Notre Dame Press, 1984, p. 6.

iii Ibid, p. 19.

iv Ibid, p. 33.

v If you're fortunate enough to not be familiar with such things as campus codes of sexual behavior, look it up. I'm certainly not advocating horrible behavior. But could we be a little nuanced in our thinking about how people actually interact?

vi Op. cit. p. 114.

vii Ibid, p. 59.

viii Ibid, p. 118.

ix Ibid, p. 156.

22 Apr 2024 | 9:31 am

3. The world out of kilter: occupation and zombification

by Paul Cudenec

The kind of society I long for is an organic one, in which people live in the way they see fit, guided by their own inclinations, the customs they have inherited and the circumstances of place.

As an anarchist, I am obviously opposed to all authority imposed from above, to any kind of formalised, entrenched power, but that does not mean that there could be no kind of moral "authority" or guidance in the world I want to see.

Traditional societies often look to village elders, wise women, and other respected individuals to help steer their decision-making.

The advice they give arises from within the community concerned and, in order to be followed, will have to correspond to a generally-shared sense that the proposed direction is the right one.

This is not the case with those who exercise power over us today. Due to the corruption of our society, authority is wielded in the interests of a group which neither identifies with the people as a whole nor is prepared to be guided by its wishes.

Instead, it seeks to impose its own agenda on the population by any means necessary – by propaganda and persuasion, if possible, or otherwise by outright deceit, intimidation and physical violence.

Even worse is that this ruling gang, which is essentially nothing but an occupying force, shares neither the specific local moral codes of the various peoples it rules over, nor the general human sense of right and wrong that would once have been shared by its own ancestors.

This is because it is a rogue element, a criminal entity, intent only on increasing its own wealth and power, and has no use for ethics.

Indeed, it takes sadistic pleasure out of using, manipulating and inverting the majority population's values – their sense of justice, their fondness for their homeland or their love of nature – in order to advance its own venal programme.

Individuals in such a society are unable to follow their own moral compass, to act according to their own innate desires, to follow their dreams, pay respect to the archetypal template in their unconscious.

This is not just because they are physically constrained, by authority, from acting and living in ways that they feel are right, but also because they have been mentally conditioned not to listen to the voice within.

They are besieged, through all their waking hours, by messaging, by propaganda that tells them they have to live, think and behave in the ways set out by the ruling gang.

A natural society will produce all kinds of individuals who complement each other in the ways that they contribute to its well-being.

There are those who are drawn to caring for others, to teaching the young, to growing, to feeding, to building, to physically defending the community, to resolving disputes and so on.

There are also the artists, poets, preachers and prophets, the antennae of the people, who are sensitive to the overall feel of the society and can sense when something is wrong.

Young people often start out with this gift – think of all the different generations rebelling, in their varying ways, against this modern world! – only to be ground down into compliance by the satanic mills of power.

But some carry on noticing and sounding the alert, with the aim of waking up the population as a whole to the danger they are facing.

It is therefore important for the ruling occupying force to isolate the small minority who remain connected to their own deep knowing and to the organic spirit of the community.

They do this by insulting, mocking, demonising, dismissing, intimidating, criminalising and imprisoning them – by presenting them, in their usual inverted manner, as a menace to the very society whose well-being they are trying to defend.

This is psychologically difficult for these social antennae, who risk being deeply wounded by a rejection that they feel comes as much from their own community as from the occupying force.

Banding together in self-defence, they can become inward-looking, cultish, and unable to properly communicate with others outside their ranks.

Or, as individuals, they can become bitter and angry with those who refuse to listen to them, dismissing most members of their community as ignorant fools who deserve no better.

In either case, they have completed the work of the ruling gang by cutting themselves off from the social organism to which they belong.

That organism therefore has no more brain, no more soul, but is a social zombie, staggering on towards its own destruction under the malevolent control of the life-sucking criminocracy.

19 Apr 2024 | 8:16 am

4. What is Propaganda?

by Mike Driver

"There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says 'Morning, boys. How's the water?' And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes 'What the hell is water?'" – David Foster Wallace

In this analogy we are all fish, I'd like to claim to be the wise old fish for the purpose of this article but the old guy is swimming in the same water as the rest of us. The thing is our sea isn't filled with water it's composed entirely of propaganda. In this late stage of corrupt oligarchic capitalism and fake democracy there literally is nothing else. It is everywhere and everything. It comprises our entire experience.

Has the western way of attending to the world made us more vulnerable to the influence propaganda?

To understand

The least thing fully you would have to perceive

The whole grammar in all its accidence

And all its system, in the perfect singleness

Of intention

WS Merwin

To understand the isolated objects and events of everyday existence we need to grasp the entire underlying basis of the entire system. We need to understand that when we pull at one piece of the universe it is attached to all the others. We need to realise that there are no simplifying causes in our complex system. To understand the smallest thing we need to understand everything. Until everything is continuous.

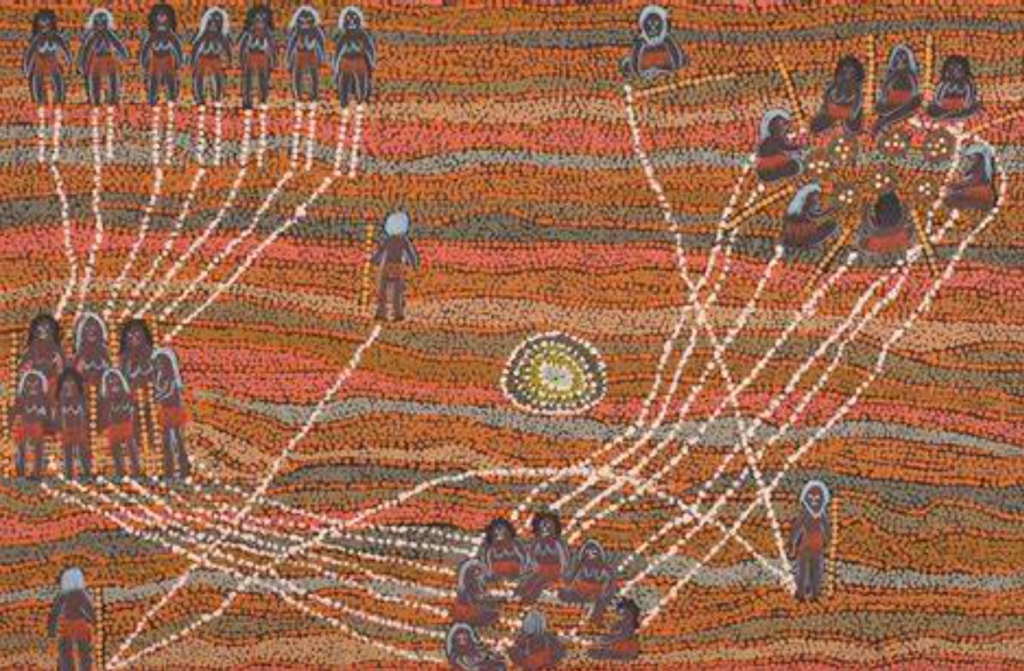

I recently visited the Kruger national park in South Africa and it is on a bush walk where you start to realise the power of trying to look at the world like an indigenous person. This is stupendously difficult for the western mind, like trying to walk headlong into a gale. The game drive is far more suited to our truncated attention span. Drive, see lion, take photo, drive, see giraffe, take photo, every encounter a small packet of transmissible information. When you walk, you notice your guide is attending to the world in a completely different way, a flow state more like a continuous and dynamic film than a static atomised photograph. A way of attending to the world that prioritises context, harmony and coherence. The herd of buffalo approach and retreat like waves on a beach, the lion print is days or hours old, the wind down or upward, this plant good for that ailment, everything attached by an invisible thread to everything else. The Pale Chanting Goshawk a verb, a bird that is goshawking not a noun frozen in time.

Over a number of hours paying this kind of attention to the wild you find yourself breathing more slowly, moving to a different rhythm, awed by the knowledge of your guide and the vast web of interconnectedness that surrounds us everywhere.

There is an entire realm of knowledge either lost or ignored. What gives us in the west the authority, the arrogance to assume we can discount these ancient ways of seeing? This is the hubris that engulfs us. Many millions of people and counting have died as a direct result of resisting the western way of knowing. A way of knowing that seeks control and believes in godlike powers of intervention. A way of knowing that sees the world as individuated separate events, parts to be manipulated. A way of attending to the world that misses the gestalt, the big picture. Is there a different way to look at what is happening to us and to understand our place in the universe? A way of looking and understanding that everything is continuous, nothing is discrete. Or are we condemned to be led by the men who live in the shadows, constantly feeding us bits of disembodied information, shaping our very perception of reality to their own ends?

The rate of change in the cultural environment, especially the digital environment, has drawn a veil over reality. The digitally minded, the reductionists, would have us believe homo sapiens is evolving in response to these changes – becoming less human, more machine-like, 'transhuman' they tell us. I suspect something even more sinister is happening.

Sigmund Freud's nephew tells us exactly what is going on:

The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country… We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of… In almost every act of our daily lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons…who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind. – Edward Bernays, Propaganda

As the familiar advice goes – when someone tells you who they are, believe them.

How then did they pollute the water?

Firstly they have taken advantage of our inability to contextualise, because we think linearly we fail to spot that the side effect of (manufactured) events is actually the intention. The propaganda of 'cause' obscures the nefarious machination.

For those with a more technical mind, Stafford Beer's concept, 'the purpose of a system is what it does' (POSIWID), provides us with some intellectual systems thinking foundations. However I don't think Stafford's idea picks up the darkness and coordination involved, so I'm running with the side effect is the intention (TSEITI):

Oh look, we inadvertently transferred trillions from all of you to the billionaire class as a result of bailing out the banks, locking the world down and concocting a fake climate crisis.

Modern Monetary Theory, Covid and Climate Change is the propaganda.

The wealth and power transfer is the intention.

Oops, all the young orthodox Christian men have been killed in the defence of Ukraine. Defending democracy in the most corrupt country in Europe is the propaganda. The meat grinder was the intention all along.

Oh dear, we've triggered a cancer crisis via those safe and effective gene therapies we didn't force on several billion people. A supposedly deadly 'virus' in 'pandemic' was the propaganda. The opportunity to fleece you for more unsafe and ineffective pharmaceuticals was the intention all along. At the time of writing it is starting to look like the intention may even be considerably worse than just mere theft as the excess death toll rises inexorably in highly vaccinated countries

The climate propaganda is particularly nefarious; the corporates spend several generations polluting the planet then pass the blame to you for driving your car, heating your house or taking a holiday.

Almost every significant historical event over the last century and a half or so becomes clearer when looked at through the side-effect-is-the-intention lens. WW1, WW2, the Russian Revolution, what were the outputs of these events? What was the propaganda that ensnared people? Why did hundreds of millions of people die? If I had the time and patience this list could be book-length. I'll leave you to work out the intention of your favourite raft of bullshit.

So what is it that is truncating our attention span, destroying our ability to see in context and to act in good conscience? In the broadest sense the enemy is media, the more digital, available and addictive this media becomes the worse it is.

And of course we are now all addicted to the crack cocaine version of media. The internet and all its bastard sons, social media, smart phones, google, fucking phone cameras, ear buds, sat nav and every smart dumb thing that keeps pulling us back to the glass vampire.

Jonathan Crary in his excellent book Scorched Earth:

"Near the end of his life, in 2007, Jean Baudrillard observed that the logic of Western modernity required that it be imposed on the entire world, that no peoples or places should escape its demands. The West, he writes, exports its economic and cultural models everywhere in the name of universality but it is a nullifying universality, emptied of any truths, leaving in its wake all that has been de-sacralized, unveiled, objectified, financialized.

"It is a challenge to the rest of the world 'to debase themselves in their turn, to deny their own values … to sacrifice everything by which a human being or a culture has some value in its own eyes.'"

The internet is the ultimate hypnotist, the purveyor of propaganda in its purest form, the creator of this decontextualised world. Your true consciousness is analogue, there is no algorithm running your mind. This is the basest of all propaganda lies. The origin of consciousness remains a mystery. All speculations of computational-like function require an even bigger leap of faith than dragging God into the debate. "Computation" is the phlogiston explanation of consciousness.

The side effect of digitising the world is to sever you from your analogue conscious mind. The truth is that relationships, time, value, purpose, experience, sacrifice, humour, love, consciousness, and the sacred are irreducible to algorithm or anything else. And everybody knows this. Meaning precedes reason.

We don't need to worry about artificial intelligence so much as we should be wholly concerned with the 'artificialising' of intelligence.

Once the world is digitised, behaviour is driven from the outside. The lie they sell you is that your unconscious desires are driving your behaviour. Bullshit, it's all propaganda: fear porn, actual porn, manufactured crisis, the science, climate malarkey, nudges, lies, trickery, deception, politics, debt, consensus, tv, Netflix, social media, education, race, employment, news, suggestion, hypnotic repetition, drugs – legal and illegal, atheism, bad parenting advice, academia, institutional subservience, centralisation, new age mumbo-jumbo, the internet, trans, psychological conditioning, behavioural science and war. All lies. Everywhere.

"The loss of memory by a nation is also a loss of its conscience" – Zbigniew Herbert

How do we shake ourselves from this hypnotic trance, how can we wake ourselves up? How can we remember what we really are?

The writer Barry Lopez tried to live his life as a 'Continuous respectful attention to the presence of the Divine'. Theodore Adorno said 'Das Leben lebt nicht' – Life no longer lives. I think he meant us. Rilke said 'Du musst dein Leben ändern' – You must change your life.

Is there anything more astonishing than waking to the morning, the slow wheel of the universe turning silently? I heard a Black Redstart while walking in the forest yesterday. It shouldn't have been there. Too early in the season. Switch everything off, it said. Switch everything off. Du musst alles ausschalten – You must turn everything off.

The ladder out of the sea of propaganda is an intense interaction with the sublime. Sublimity is pure context, it is absolute consciousness. Have you ever woken in the early hours, a storm raging outside? Have you been moved to absolute silence by the beauty of a sunrise or sunset? Can you put your phone down for long enough to become that moment yourself? This can only take place in the absence of artificiality.

Complete disconnection is the only answer. We must turn the internet off. If this sounds too radical please tell me what your freedom is worth, what your soul is worth.

I think we can all sense something: like music from very far away or the light from a JMW Turner painting. Something like a memory not made yet or the warmth from a log fire when you walk in from the cold. Something calling your very soul: 'come home, come home', it whispers, 'this isn't the life you intended'.

Listen. The old world is waiting for you, 'still spinning its one syllable between the earth and silence'.

17 Apr 2024 | 10:14 am

5. Good Cities, Good Citizens, and Good People (Revolutionary Aristotelianism Part 3)

by W.D. James

A modern-day warrior

Mean, mean stride

Today's Tom Sawyer

Mean, mean pride

Though his mind is not for rent

Don't put him down as arrogant

His reserve a quiet defense

Riding out the day's eventsi

– Rush, Tom Sawyer

Aristotle had begun his Politics with the assertion that human activity is aimed at what is at least perceived to be good. As that work develops, it becomes clear that Aristotle's activity is itself an example of his principle: he is interested in uncovering what constitutes the good of cities, of citizens, and of people.

Good Cities

He sets out to create a basic typology of the possible forms of government or of how political societies may be constituted. We can imagine this in the form of a chart with two axes. The first axis is based on a strictly empirical observation: how many people rule?

| Rule by how many? |

| One |

| Few |

| Many |

He distinguishes between rule by one person, a few people, and by many people. The other axis is the fundamental normative distinction between whether it is a good government or a bad government, or as Aristotle puts it, between a true or ideal rule on the one hand or a perverse rule on the other.

| Normative Distinction | True or Ideal | Perverse |

What is behind this moral distinction of ideal vs. perverse rule? As we saw in the previous essays, the life of a city is one of sharing or community. Further, the proper aim nature has prescribed for life in community is the 'common good'. This is the basis of Aristotle's moral distinction: true or ideal forms of government are those that are genuinely seeking the common good; perverse forms are those that seek only the good of those ruling, at the expense of the polity at large (hence they pervert the natural order of things).

We start to 'fill in' the typology by starting with the 'perverse' side of the normative axis:

| Rule: | True or Ideal | Perverse |

| One | Tyranny | |

| Few | Oligarchy | |

| Many | Democracy |

One person ruling in their interest at the cost of the whole is termed tyranny. Aristotle, observing the various polities of his world (but seems it would hold equally true of the polities of our world), held that the fundamental conflict in all polities was between the rich and the poor. Oligarchy is the few rich exploiting the rest of society. We might be a little shocked that Aristotle places democracy on the perverse side of the table. In his view though, this represents the many poor having attained supremacy in a polity and ruling in their class interests, which is also not the common good.

We can finish the picture by filling in the true or ideal column:

| Rule: | True or Ideal | Perverse |

| One | Monarchy | Tyranny |

| Few | Aristocracy | Oligarchy |

| Many | Polity | Democracy |

True rule by one person, in the interests of the whole, earns the title of monarchy. Government by a few virtuous people in the common interest is an aristocracy. What of this oddly named true rule of the many? Aristotle simply calls it polity, or government, per se. It is different from the prior two true forms in that it does not rest primarily on the virtue of the rulers, though it will take care to instill virtue in the citizenry. It is a product of political art or skill. For Aristotle it is achieved by crafting the constitution so that the power of the few rich is balanced by the power of the many poor: both may still act in partisan fashion to achieve their class interests, but the constitution is balanced in such a way that the outcomes will balance their interests, producing good, common, results.

Any of the forms of government in the left column technically constitute 'good government' in that they succeed in pursuing the common good. Also, Aristotle does not think any one form of government is possible in all circumstances and also those circumstances will determine what form of government is called for. For instance, the ancient Spartans needed to reform their polity. It so happened that a very virtuous individual was at hand to govern for them, so they did well in asking Lycurgus to legislate for them. However, he does seem to think that polity is a flexible and versatile form of government that can be serviceable under many different sets of circumstances.

Good Citizens

Aristotle does not take the concept of 'citizen' lightly. He recognizes different polities will look on it differently and define who is a citizen more or less broadly. However, since government serves a role in helping us achieve good lives, one would need to actually participate in governance to fully receive all those goods. Hence, "The citizen in this strict sense is best defined by the one criterion that he shares in the administration of justice and in the holding of office."ii

We start to see more why Aristotle saw the relatively small city-state as ideal. He holds that any sort of passive citizenship, citizenship that just consists in being ruled, is not adequate. He held that to become fully developed human beings, citizens needed to learn how to obey and how to rule. He felt age was a natural basis for this distinction. The young and inexperienced should learn to obey. It should be noted that this is not a submissive or oppressive obedience. They should learn to obey so that they might learn to rule. Children should obey their parents, students their teachers, etc… However, the role of the people on the top of those hierarchies is to equip the subordinate to take on their responsibilities and exercise authority in the future. Then, when they are older and have come into full intellectual and moral stature, they should rule: that is, they should participate in the administration of justice and the holding of offices.

It's a participative view of citizenship. In administering justice, one develops one's moral awareness: what is just and unjust, how to apply that to particular cases, what is the objective of punishment, how should goods be distributed in the community, how to distinguish between just and unjust wars? And one should take on the responsibilities of governing, of administering to the common good. One who does these things will grow in goodness according to Aristotle.

Good People

Good cities are good because they produce good and happy people. Aristotle, like most classical writers, pays a good deal of attention to the role and character of education in the maintenance of a good polity. It is worth noting that he is, as far as I am aware, the first proponent of public education: education at public expense. The broader the base of the citizenry the broader the number of people who need to be well educated. The city cannot afford to have its citizens govern poorly because they were too poor to afford an education.

But what counts as a good person? Aristotle observes: "Anyone who is going to make a proper inquiry about the best form of constitution [meaning the overall structure and institutions of a society, not particularly a written constitution] must first determine what mode of life is most to be desired."iii In his account of his teacher Socrates' trial, Plato (who was in turn Aristotle's teacher) reported Socrates admonishing his jurors and fellow citizens that they made the mistake of valuing exterior things like wealth and prestige above the "care of your souls". He said this was a case of putting the lower above the higher because the possession of a virtuous soul would help bring about external goods, while the possession of external goods does nothing to improve the virtue and health of the soul. A rich but foolish person is just a schmuck (Yiddish had not developed as a language by Socrates' time, but if it had, I'm sure he would have made liberal use of Yiddish terms). Directly paralleling this, Aristotle states "You can see for yourselves that the goods of the soul are not gained or maintained by external goods. It is the other way around."iv

Aristotle deduces from this that the essential thing is to develop one's character and soul. Of external things, one needs a sufficiency, but to continue to put effort into increasing external good is probably to shirk the internal. So, we want citizens to value the right things and strive for those. Aristotle believes, then, that the city should also follow the same set of priorities. Externals in this case would be things like acquiring colonies, military ventures, etc…. The city must make provision for these, it should not be a sheep amongst wolves, but there is a strict limit. It should instead focus on developing its internal goods like its culture and the development of citizens.

To do so, individually or socially, is, on Aristotle's reckoning, to become god-like. Aristotle's god is rather peculiar. He is certainly not a 'personal god' either in the sense of having a personality or of relating to humans (or anything else for that matter) on a personal level. He is the "unmoved mover" whom Aristotle feels compelled to deduce from the nature of nature. All things have a cause (or, well, four causes). So, if we were to hypothetically reason backward from all that is to what caused it, and then what caused that, and what caused that, we either end up with an infinite regress which makes no sense, or we have to say there was a first cause. Well, as any four-year-old would know, that provokes the question 'what caused the first cause?' Well, nothing because to be the first cause means there are no earlier causes. So, we have to have something that causes without itself having been caused: the "unmoved mover" (by which Aristotle means the uncaused causer).

He continues on: "God himself bears witness to this conclusion. He is happy and blessed, but he is so in and of himself, by reason of the nature of his being, and not by virtue of any external good."v Why is that? We have to look rather closely. God, by definition, was not caused. God then is the first cause of all else that comes about. God could not have been in need of anything because he is self-sufficient. Being self-sufficient, he might then set about to act (create) or not. That ancient Greek wonder that there is something rather than nothing is pulsing through Aristotle's mind here. God may well have just Been. But, as it turns out, God set things in motion; he Did. So, God must be happy and blessed because he lacks nothing; he is all he needs to be in and of himself. The externals, the stuff he set in motion, are not much of a concern to him: he does not need them.

Aristotle is suggesting that to become like this (to the extent we are capable of it) is the key to happiness. Focus on what you are more than on what you do or what you have. Be of such sure character that nothing much is going to 'move' you. We all know people more or less like this: they are legitimately self-assured. They know what they are made of because it has been tested. From this rock-like position, you may then set external things in motion. But they are not your ultimate concern.

This is the distinction between the life of contemplation and the life of action. The life of contemplation, focusing on the interior, is superior. Hence, it is what the polis should aim at for its citizens. But, wait, that doesn't quite work! Hadn't Aristotle spent most of the Politics telling us how citizens, in their shared lives together working toward the good should be actively engaged in the administration of justice and the holding of offices? That's 'external' stuff. The 'life of action' stuff.

Aristotle gets that there is an issue here. He admits: there is a difference between a good 'man' and a good 'citizen.' There may be a lot of overlap, but they are not one and the same. Well, what the heck are we supposed to do—aim for being good citizens or good people? Aristotle offers no easy answers. We must live together, that is our nature, so we cannot say it is not good to be a good citizen. However, we are each a person as well and must seek our good (not our individual self-interested good at the expense of the social good, but the real good of an at least quasi-spiritual existence). They are different.

I'm going to be extremely speculative here, but that has never stopped me before. We know from Plato that what he taught to his students at his Academy was not what he wrote in his written works. They are not textbooks for his students. All his actual teaching was in the form of verbal dialogue with the students and we have reason to believe the doctrines developed and taught there were not exactly identical to the teachings of his written works. Aristotle spent 20 years studying with Plato before he went and formed his own school, the Lyceum. Either he was very dense (20 years to complete college) or he was very thorough. My guess is that Plato taught a whole lot about the teachings of his teacher, Socrates, to his students—way more than is written down in any book by any author we still possess.

From the little we know of the historical Socrates from the writings of Plato (again, probably way less than Aristotle would have known), he seems like a great model of how to bridge this gap between the good citizen and the good person. I will briefly recount three stories about Socrates that Plato recounts for us.

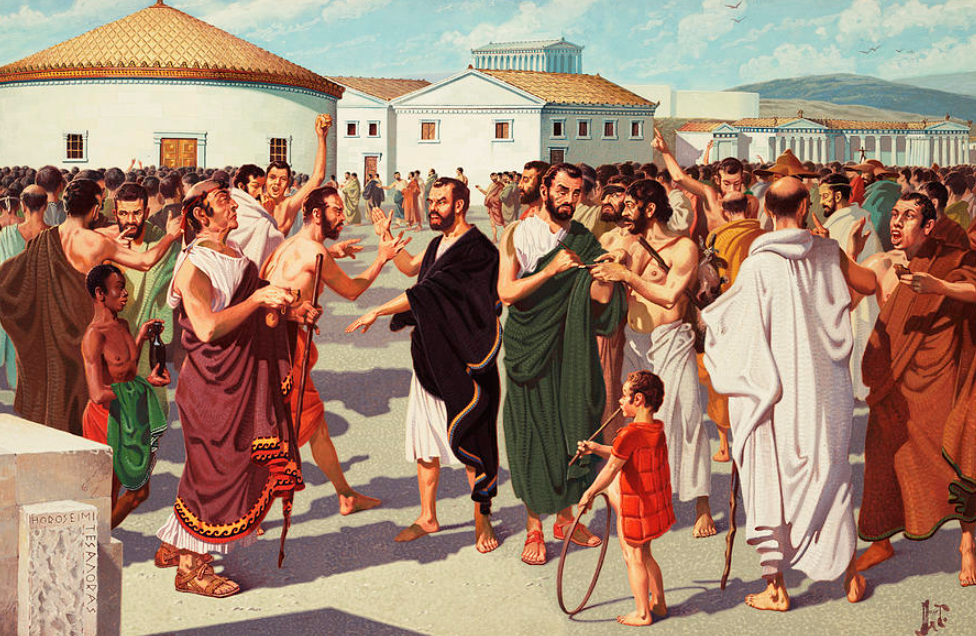

We are told of Socrates' life as a soldier. This was the epitome of citizenly duty. Socrates was apparently of middling economic status, as we know he was able to afford to outfit himself as a Greek hoplite. These were the heavily armed, well-disciplined infantry that was the backbone of any Greek fighting force. If you were rich, you would be in the cavalry so you didn't have to walk so much. If you were poor, you'd end up rowing a galley (well, mostly slaves did that) or being the sort of infantry who were completely expendable and almost as useless.

While on campaign, for instance, we know Socrates fought at the battle of Potidaea in the Peloponnesian war. Socrates was known as a good but weird soldier. We are told that he was very hardy, traveling barefoot and lightly cloaked, even in inclement weather. He was brave and did his duty. However, while on the march, he would sometimes stand motionless, lost in thought, for up to the better part of a day. That has the ring of self-possession first, then determined action when needed.

Secondly, Plato has Socrates tell us in his trial about how when he was ordered by the Thirty Tyrants (the hated quislings set up by Sparta to govern Athens after the latter's defeat), when it was his term to hold office, to carry out a sentence which he felt was given contrary to the law, he refused. He just didn't do it, at the risk of his own skin. In that case fate was on his side as the democracy was restored before the Tyrants could do much about it. Again, sort of a passive sticking to justice and the law at risk to oneself. Citizenship yes, but moral integrity (and even political integrity, as the orders were contrary to the law) first.

Thirdly, Socrates's trial itself. Having been convicted by 500 jurors of his peers (that is what democracy looks like), he refuses to back down and 'play the game' when it comes to his sentencing (hence, he gets death). He will not betray genuine justice. He lectures his condemners for their own good (the speech about the goods of the soul referenced above). The good citizen as martyr to integrity.

I would suggest that in Aristotle's mind, Socrates had navigated this gap between being the good citizen and the good man as well as it could be done. And yet, Athens killed its most valuable citizen. Ultimately, at the heart of political life is tragedy. The good of society and the good of individual human persons are not easily reconciled. The good person does their best as a citizen, but their ultimate loyalty lies higher. Wise cities would recognize the rightness of this. Very few existing cities are so wise.

Of Oligarchs and Good People

I think we know what it is to be governed by oligarchs. Aristotle helps us to understand where their perversity lies. Under such circumstances, the conditions for producing good citizens is not only limited, but actively undermined.

This is no light matter. We are political animals. To remove the opportunity for participative self-government is to damage our humanity. Yet, we may certainly strive to be good people living under a bad regime. To echo the lyrics of Rush with which we began, the good person's reserve harbors a "quiet defense." She may ride out the "day's events" as Socrates rode out the times of the Thirty Tyrants. But this is clearly a non-ideal situation.

In following essays, we will turn to the thought of the contemporary Aristotelian thinker Alasdair MacIntyre. He will help us focus our critical insights on the effects of our modern disorders and will suggest how we might go about recapturing something of a good community life as well.

i Alas, Rush was my first concert experience. A bit much Ayn Rand, but pretty solid tune: Rush – Tom Sawyer (Live Exit Stage Left Version) – YouTube

ii Aristotle, Politics, translated by Ernest Barker, Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 85.

iii Ibid, p. 251.

iv Ibid, p. 252.

v Ibid, p. 253.

15 Apr 2024 | 9:50 am

6. Clarity and focus

by Paul Cudenec

At the end of 2022 I brought out a 100-page booklet entitled 'Enemies of the People: The Rothschilds and their corrupt global empire'.

To be honest, I was a bit apprehensive about publishing it, as I knew that it would probably lead to me being labelled not just a "conspiracy theorist" but an "anti-semite" as well.

This did actually happen, despite my insistence right at the start of the booklet that "I am not singling out the Rothschilds because they are Jewish, but rather in spite of that fact".

Before publishing it, I made very sure that I was completely certain about everything I stated.

I was confident that I had marshalled enough facts and reliable historical analysis to demonstrate the reality of the very disturbing situation that I presented in the final section:

"The Rothschilds have, as I have shown, amassed vast wealth at the expense of the rest of us, consistently put themselves before others, profiteered from war after war, grabbed hold of industrial infrastructure, exploited humanity, destroyed nature, corrupted political life, used royalty for their own purposes, privatised the public sector, imposed their global control in a secretive manner and now imagine that they can dictate our future, confining us to a miserable and denatured state of techno-totalitarian slavery".

Nothing I have seen or heard since then has cast any doubt on this conclusion.

In fact, I have merely come across further nuggets confirming the central role of the Rothschilds in the global criminocracy, such as in my November 2023 dive, sparked by Ben Rubin's work, into the sinister world of 'Tony Blair and the Rothschilds'.

Independent journalist Sonia Poulton brought out an excellent video report on the same subject at around the same time.

Incidentally, the strange political continuity between Margaret Thatcher ("Conservative") and Tony Blair ("Labour") is easier to understand when you discover the closeness of both British politicians to the Rothschilds.

With regard to the former, the Bloomberg obituary of Evelyn de Rothschild declared: "His friendship with Margaret Thatcher – British prime minister from 1979 to 1990 – helped the bank win the job of lead underwriter in the sales of shares in stateowned companies such as British Gas Plc and British Petroleum Plc".

Somebody has kindly pointed out to me that Rothschild involvement in planning the privatisation-by-stealth of the NHS is mentioned in the 2022 documentary The Great NHS Heist (8 minutes in).

I have also stumbled across a couple of references to the Rothschilds in the writing of respected anarchists from previous centuries.

I quoted Mikhail Bakunin's comments about the compatibility of Karl Marx's viewpoint with that of the Rothschilds in 'The false red flag'.

And I was also interested to find this quote from the Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta:

"Today, government, consisting of property owners and people dependent on them, is entirely at the disposal of the owners, so much so that the richest among them disdain to take part in it. Rothschild does not need to be either a Deputy or a Minister; it suffices that Deputies and Ministers take their orders from him".

Anyone who imagines that this is no longer the case today, and that the Rothschilds somehow lost the vast power they once wielded, has been fooled by their sophisticated self-concealment.

The same goes for people who are aware of the role of the Rothschilds but who imagine that they are just one of several big powerful families and are on even footing with the likes of the Rockefellers.

I am not alone in my conviction that other billionaire clans have for many decades now been subsidiary to the Rothschilds.

One suggestion, often encountered on Twitter/X, is that the Rothschilds are in fact just a front for an even murkier network of old European artistocracy linked to the Roman Catholic Church.

My doubts regarding this particular theory have led to one or two strange accounts getting quite angry with me, accusing me of being "controlled opposition" and, by focusing on the Rothschilds, "diverting attention" away from the "real" rulers of the world, whom they never seem to actually name.

I feel this issue has now been satisfactorily cleared up by events in Gaza – or rather by the lack of humane reaction to events in Gaza by governments across the world.

It is obvious, from the carte blanche given to Israel for its genocidal activities, and from the smearing of anyone daring to speak out against the bloodbath, that the global criminocracy is aligned with Zionism and Israel.

This remains true even if, as seems possible, US/European complicity with these crimes is intended to facilitate the transfer of global geopolitical power to the BRICS-dominated "multipolar" version of the New World Order.

No family is more closely associated with the Zionist/Israeli entity than the Rothschilds.

The Balfour Declaration of 1917, in which Britain expressed the intention of helping to create a Jewish state, was actually addressed to Lord Rothschild and, as Ben Rubin explained on UK Column in March this year, Yad Hanadiv, the Israeli version of the Rothschild Foundation, was "the funding vehicle behind the design and build of the Israeli Supreme Court and Knesset, and was intimately involved in the establishment of the Israeli state".

Since the global criminocracy has revealed itself to be clearly Zionist, the fact that the Rothschilds are so dominant within Zionism constitutes, by itself – even without all the rest of the copious evidence pointing that way – confirmation that they are likewise the dominant force within the global criminocracy.

To be clear on this point, this does not mean that "the Jews" control the world. Most Jews control nothing at all beyond their own personal lives, just like the rest of us.

It is important to very specifically refer to the Rothschilds in order to avoid a merging of the notions of Rothschildian power and "Jewish" power which only helps the Rothschilds to hide their own responsibility behind a fog of anti-semitism, whether real or merely alleged.

Simply to talk about the Rothschilds – about what they have done, what they are doing and what they plan to do – is to start challenging their activities and their dominant status.

Their system only works through the unsuspecting complicity of millions of people who don't realise what masters they are ultimately serving.

Because of this, the Rothschilds don't want the extent of their influence being generally understood, preferring us to focus on the activities of particular individual puppet-politicians; on "rival" nation-states or power blocs within their global system; or on the various ideologies – "capitalism", "communism", "fascism", climate-based "environmentalism" – that all prop up the state-industrial "development" agenda essential to that system.

The flood of "hate" laws being introduced across the world, seeking to prevent so-called "online harm", is, I suspect, largely a response to growing public awareness of the nature of the criminocratic system.

They're worried that we're on to them and will refuse to go along with their nefarious plans.

In the 19th century, when the Rothschilds took less care to conceal their wealth and power, they were met with not only written but physical attacks from angry people – particularly in France.

During the 1848 uprising there, insurgents targeted the industrial rail infrastructure with arson and sabotage, particularly the Rothschilds' massive Nord network – a section of their line near Paris suffered more than a million francs of damage – and a Rothschild chateau in the Parisian suburbs was set on fire! [1]

And in 1895 a home-made letter bomb was sent to a Rothschild address in France, prompting The Times in London to comment: "An Anarchist outrage on one of the Rothschilds is not greatly to be wondered at. In France as elsewhere they are so wealthy and hold so prominent a place that they stand out as the natural objects which Anarchists would seek to attack". [2]

Rothschild offices have also been targeted on several occasions by the Gilets Jaunes (Yellow Vests), a 21st century popular insurgency that brought so much hope to so many of us from 2018.

In 2019 protesters wrote: "Rothschild! Give the money back!" on the road outside the bank in Lyons.

Then in April 2022 a group of Gilets Jaunes walked into the Rothschild premises in Paris and denounced the role of President Emmanuel Macron in a big-money deal involving Nestlé and Pfizer, while he was (openly, at the time!) a Rothschild employee.

It would be encouraging to see similar actions happening in the UK, whether at Rothschild HQ, New Court in London, or at Waddesdon Manor, the country mansion in Buckinghamshire (pictured below) used by the Rothschild Foundation for its secretive and undemocratic meetings deciding, behind closed doors, the future direction the country will be taking (see, again, the UK Column report).

The idea of protesting at a country mansion isn't as outlandish as it might seem.

When I was still living in England, I was involved in a couple of protests at Wiston House near Steyning, West Sussex, which is home to Wilton Park, the secretive UK government venue that boasts: "We convene world-changing dialogues".

Just to give you a flavour, recent 2024 events have included "Towards 2030: Transformative actions and partnerships to deliver the SDGs" and "Building the enabling environment for Ukraine's economic growth: the role of its reform agenda".

I was also part of a huge crowd demonstrating outside a luxury country hotel near Watford when it hosted the 2013 Bilderberg meeting, yet another secretive gathering of the "public-private" mafia.

A fellow campaigner and I seized the opportunity to hand out leaflets and chat to people to encourage them to come to our Stop G8 protests in central London a few days later – an uphill struggle given the baffling mutual suspicion between two groups of people opposing different gatherings of the same global criminocracy.

So what would be the focus, the "hook", of any future UK protests against the Rothschilds?

Reasons to oppose them are hardly in short supply – personally speaking, their role in fabricating and prolonging the First World War still makes me angry, 110 years on! – but what would be the one likely to attract most support?

I don't think we currently need to look any further than their aforementioned proximity to the Israeli state which is currently committing genocide in Gaza – and in particular their role in corrupting British democracy not just in the interests of their private business, but in the interests of a foreign state.

Quite a powerful wave of voices opposing Zionism and its insidious political influence is now emerging in the UK – I am thinking of the likes of David Miller, Peter Oborne, Asa Winstanley, Lowkey, Tom London, Craig Murray, Mark Curtis, Matt Kennard and Andrew Feinstein.

Importantly, in view of the smears that are always rolled out, many anti-Zionists are Jewish and their continuing involvement should be celebrated and encouraged.

Is it inconceivable that a protest movement against Zionism in general could start to home in on the Rothschilds in particular?

[1] Jean Bouvier, Les Rothschild (Brussels: Editions Complexe, 1983), p. 142.

[2] Niall Ferguson, The House of Rothschild: The World's Greatest Banker 1849-1999 (New York: Penguin, 2000), p. 271.

10 Apr 2024 | 10:01 am

7. The Coming to Be of Society (Revolutionary Aristotelianism, Part 2)

by W.D. James

We sang the songs of childhood

Hymns of faith that made us strong

Ones that Mother Maybelle taught us

Hear the angels sing alongi

– Will the Circle Be Unbroken, Roy Acuff's lyrical adaptation

For the duration of the classical period, the Greek philosophers were able to retain a marvelous appreciation for the bare fact of existence. Why is there something instead of nothing? Plato famously said that philosophy was born of wonder. Further, why is it that when we look about there's all these things? How do they come to be? The Greeks pretty much assumed some sort of primordial chaos (they were really not able to conceive of creation from nothing, a staple of the cosmology of the Abrahamic faiths). But chaos never remained chaos. It was mysteriously propelled toward order. A particular order might decay, and we might refer to that as chaos (a political society that devolves into civil war between competing warlords, for instance), but it's never full chaos. The Greeks could theorize full chaos, it would be right next door to non-existence, but we never really encounter it. It is a universe of things, not of chaos. Systems form (galaxies, solar systems, organisms, social systems). As we might say, complexity evolves.

For things to be things, and not just stuff, they have to take on form. There is the stuff things are made of, but then there is the form which makes the thing the discernable thing that it is (a dog, an atom, a beret). Plato is the archetypal philosopher of Being, of the form of forms. Aristotle is the philosopher of Becoming, of how the stuff becomes the things it becomes. As such, he is also the philosopher of the cause of social things—how associations come to be.

Causation

The Greeks can be wonderfully nuanced. To ask how (and for Aristotle, we may also ask why) something comes to be is to ask: what caused it? When we moderns answer this sort of question, it usually takes the form of: X did such and such, which caused Y to do such and such. What caused the 8 ball to drop into the corner pocket? The pool cue struck the 2 ball in such and such a way, which, operating under Newton's laws of thermodynamics, moved with a certain amount of energy, which upon striking the 8 ball produced an equal and opposite reaction such that the 8 ball travelled across the table at a calculable speed, dropping (due to gravity) into the pocket.

So, if we asked how a person sank the 8 ball, the account would look more or less like that. Similarly, if we are talking about the coming to be of biological organisms. Well, Ralph's mommy and daddy met and liked each other, and then something about birds and bees, supplemented with something about genetics, and then some stuff about wombs and birth canals and that is how Ralph came to be. Aristotle would say, 'yes, well and good. However, that account is ¼ of a full account of how something was caused to be and it's not even the most interesting quarter.'

On his account, whenever something comes to be, there are four types of causation involved, all operating simultaneously. The sort of accounts given above he termed 'efficient causation.' There are also 'material,' 'formal,' and 'final' causation. By material causation Aristotle meant what kind of material is involved (he wasn't an atomist and held to a qualitative view of different sorts of matter). By formal causation he meant what caused it to take on the form it did (by including genetics in the above account, we pulled in something like formal causation).

But the really exciting thing, and the thing that will make us twist our reductive modern minds to see it, is final causation. This sort of represents a chronologically backward form of causation. We might want to just say that can't be, but in a universe that (as revealed by modern physics) involves causation (or action) 'at a distance', which quantum mechanics and field theory have had to try to account for, maybe it's not too weird.

To try to get our heads around this, we will start with an account that is overly simplified and not really Aristotle's view, but which I think will help us get to a better account (rather tongue in cheek). We start with the example of the perennial philosophical puzzle: which came first, the chicken or the egg? Plato answered, 'neither; the abstract form or idea of the chicken came first.' Aristotle answered, 'the egg came first…..but it wanted to be a chicken.' That is, the chicken (which chronologically comes later), is the cause of the egg (along with the efficient, material, and formal aspects) in some real sense. The egg wants to be a chicken; its purpose (or 'end') is to become a chicken. Further, the meaning of the egg is found in its aspiration towards being a mature chicken.

The whole point of Aristotle's science, his account of causation, really turns on this inclusion of purpose and meaning. These are absolutely banished from consideration in modern science (we will see some of the ramifications of this toward the end of this essay). He is not going to give us an account of nature that is devoid of purpose and meaning, which has subjected we moderns to no end of angst, anguish, and nihilism.

However, I would suggest this is the substance of our 'common sense'. We talk all the time as if natural processes have a purpose and meaning. Even evolutionary biologists constantly slip into this sort of talk. 'The such and such snail evolved the ability to secrete a viscous substance to aid it in scaling vertical surfaces.' They will then correct themselves to get in line with natural selection via random mutation: 'I was only speaking metaphorically, of course it was an accidental mutation that just so happened to increase the snail's ability to ascend vertical surfaces, thereby adapting it better to its environment and enabling it to better survive, reproduce, and pass on that mutation.'

Further, Aristotle's naturalism includes a normative component. Let's see how. To cut to the chase (pun intended), thoroughbred horse fetuses have a final cause of becoming thriving thoroughbred horses (of course I use horses as the example, it's a Kentucky thing). For Aristotle, every living thing has an inbuilt propensity to become a fully developed, flourishing example of what it is. If all goes right it will succeed, if it goes wrong, maybe not. If Sally the Thoroughbred gets all the nutrition she needs, avoids illness and disease, and grows into maturity, she will invariably become a healthy adult thoroughbred (she will under no circumstances become a chicken, a toaster, or a palm tree). She will be strong, swift and well-tempered. We will say of her, 'she is a good horse' and anyone who knows horses will know what we mean. If something goes wrong along the way, she may become a bad adult thoroughbred. If we wish to spare her feelings, we will say 'she's an ok horse'. And we'll all know what we mean. The important thing here is that the (at this point non-moral) terms 'good' and 'bad' have an objective meaning and they are rooted in nature (the species nature of thoroughbred horses). We have an account of nature that is purposive, meaningful, and normative. Aristotle rocks!

Souls

To get just a bit more of Aristotle's theory in before we turn to the question of society, let's talk about souls. Aristotle says there are three basic kinds (if he prefigures Gaia theory, there would also be a world soul): plant, animal, and rational. Aristotle is a materialist, but his matter is infused with soul (psyche). You can't separate soul out from body such that it would make sense to talk about a soul living after death or anything like that, but soul and body, though always united in life (both eventually go away in death), are conceptually distinguishable. By 'soul' Aristotle basically means the characteristic pattern of life of a thing.

Plants, with their plant souls, grow and reproduce. That's pretty much it. Animals grow, reproduce, and move.

Critters with rational souls (and Aristotle also defined us as "rational animals") grow, reproduce, move, and worry about it. That is, their final ends (aim, purpose) become a subject they can contemplate and will have to make decisions about. So, when we set about worrying about what our purpose and aim are, Aristotle thinks our reason shows us the answer. He says it is to be happy. By 'happiness', he does not just mean pleasure. He means flourishing, to fully actualize the potential of our being.

Aristotle thinks this is the right conclusion because anything else we could propose doesn't turn out to be the final purpose. We might want money. Why? So that we can buy things, be secure, etc… It's not just to have the money, it's to have what the money can bring. Ultimately, because we think it will feed into our happiness. We might want power. Why? Similar story, it's not the power, per se, it's how we can use the power. Why do we want happiness???? To be happy. Ultimately, all the other things we might want, we want because they will contribute to our happiness. Hence, the final end of rational creatures is happiness. All that we do, all the goods we seek, are because they will (or we think they will) contribute to our happiness. Further, to fill out a theme from last time as well, we can better see what is the essence of our desiring: the love and longing for happiness.

Characteristic associations

For Aristotle, at least when the question is about politics, there are three characteristic forms of association people engage in. As we saw last time, we engage in any of these associations because we believe they will help us achieve something good. We now have the objective criteria of that: they will bring us more happy, more flourishing, lives.

The family

He begins his discussion of forms of association: "In this [the study of political association], as in other fields, we shall be able to study our subject best if we begin at the beginning and consider things in the process of their growth. First of all, there must necessarily be a union or pairing of those who cannot exist without one another. Male and female must unite for the reproduction of the species – not from deliberate intention, but from the natural impulse, which exists in animals generally…".ii

Hence, of necessity, we have families. How so of necessity? You don't get humans to go about associating in any other ways unless you have humans associating in the reproductive way. It's important that Aristotle notes that this might not be our intention with forming a family, but it is nature's intention. Nature has its ways. Families will be formed. Humans just keep doing it, here, there and everywhere. For Aristotle the empiricist, that's the natural story then. The efficient cause is something like the story told above about Ralph. The material cause is male stuff coming together with female stuff. The formal cause is that a structure capable of reproducing, nurturing, and bringing to maturity children will take shape. That will look different in different placesiii, but any place that succeeds in replicating itself with new humans will have a version of it.

The final cause, or purpose and meaning, is to reproduce the species (we might have all sorts of other goods we are seeking as well, sexual satisfaction, intimacy, economic security, whatever, but what Aristotle sees nature doing is keeping the species going). Further, we will seek these out because we believe they will contribute to our happiness. But our happiness, flourishing, is not complete in the family.

The village

Families are not self-sufficient. Therefore, they are not the highest or last form of human association. Our society must continue to grow. "The next form of association," he continues, "which is also the first to be formed from more households than one, and for the satisfaction of something more than recurrent daily needs—is the village."iv He goes on to explain that we form villages that we might live well, by which he basically means materially. We will have greater security, we can work with others, possibly trade a bit, maybe specialize a little bit—live better. In terms of the efficient cause of villages he recounts several ways in which villages spring up from the associating of several families. The material cause is families. The formal cause is the basic form of the village which does not vary so much from Croatia to Siberia to Ghana. The final cause is the living well objective, the betterment of our material lives through shared endeavor.

The polis

Aristotle continues: "When we come to the final and perfect association, that formed from a number of villages, we have already reached the city [or polis]. This may be said to have the height of full self-sufficiency; or rather we may say that while it comes into existence for the sake of mere life, it exists for the sake of a good life."v The efficient cause is the villages in proximity to one another joining together. The material cause is the villages. The formal cause is the structure of a city. The final cause he says is the "good life". He means something quite different by this than by "living well" in a village. While a city might further the security and cooperation present in the village, it adds a qualitatively different element. We are now in the area of goodness, or morality. In addition to other things a city will afford us, it allows us to reason with one another about Justice. We will have to collectively decide how we are going to live together. What will be permitted and what not? How will responsibilities and rewards be distributed? What is owed to whom? Why be just? — so that we may be happy.

In political terms this manifests itself in the norm of 'the common good,' which we will look at in more detail next time. It also means that together we govern ourselves. Here is where our communal moral lives are integrated into the overall human aim: flourishing lives that have developed all of our innate potential such that we may be fully happy. This is the sense in which the city is self-sufficient: it is the smallest entity in which we can be fully and gloriously human. As political animals, the city has drawn us along from seeking mere life, to living well, to living good lives.

Ah, bigger is better then for Aristotle? To a point. To the exact point of the self-sufficient city-state composed of several villages. And beyond that? Beyond that, you might secure the goods of social life to some extent (the Roman empire is probably more secure from foreign invasion than just the city of Rome would have been). However, you start losing aspects of goodness quite quickly. No longer can all the citizens participate directly in the rational pursuit of justice together; more and more people are just subjects, who will not actualize the goods of political association and, hence, fail to fully develop their human potential as well.

Also, we might note that there are a plethora of other associations for Aristotle, but they are not expressly related to the city. We form friendships, canoeing groups, organized crime syndicates, and all sorts of other things to try to obtain various perceived goods. When we get to MacIntyre, he will be more interested in this wider array of associations.

Banishing final causation

The thinkers who initiated the modern project, such as Thomas Hobbes in theorizing the modern state and René Descartes (the guy who doubted everything except that he was thinking) in theorizing the modern self, quite overtly and forthrightly set their philosophical sights on Aristotle.

This is usually presented as a story of liberation from the intellectual constraints of 'scholasticism.'vi Is that really how things worked out though? Essential to their task was especially to banish any conception of final ends. You see, those imply a human nature and an objective human good and have vast implications for our social lives. I will not have time to unpack all of this, but the medieval theorists had deduced from Aristotle's conception of 'the common good' all sorts of moral constraints on individuals' pursuit of their individual goods at the expense of the shared common good. Things like restraints on lending money at interest, rents, property rights, etc…, etc…

A slightly suspicious person might suspect the moderns were looking to undercut society's defense of the common good to free up some particular set of people's pursuit of their individual goods.

i A performance by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, with Roy Acuff, Johnny Cash, and others: Nitty Gritty Dirt Band – Will the Circle Be Unbroken [Live] – YouTube

ii Aristotle, Politics, translated by Ernest Barker, Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 8.